Abstract

In a world increasingly reliant on data, automation, and systems thinking, law enforcement agencies represent some of the most complex operational machines ever built. Among them, the New York Police Department (NYPD) stands as a giant, not just in size but in layered responsibilities, real-time decisions, and massive technological infrastructure.

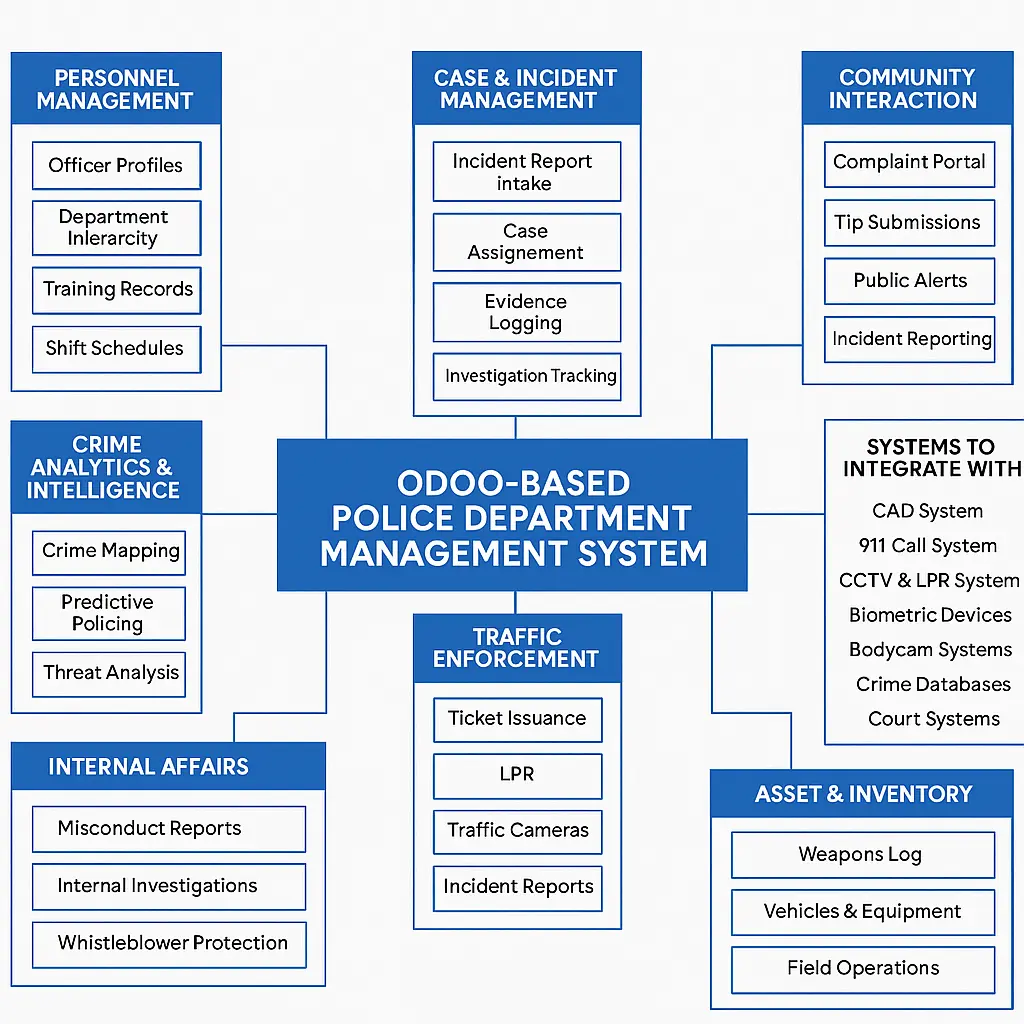

This paper is not a claim that Odoo, a modular open-source ERP system, can run an operation like the NYPD on its own. That would be unrealistic. Instead, this is a structured exploration, a design journey that uses Odoo to investigate what parts of such a large, real-world system can be simplified, modeled, and rebuilt thoughtfully.

We begin with Phase 1: Public/Officer Incident Reporting System. A foundational process in the life of every case. We study the NYPD as it stands, understand its scale and structure, and then take our first step into building a working model. Along the way, we document where Odoo fits well, where it breaks down, and where custom-built solutions will eventually be necessary.

This whitepaper is a beginning. Not a solution. Not a claim. Just focused action and a small window into what happens when consultants step into systems thinking, not to sell, but to understand.

Table of Content

1.1 Size and Personnel

1.2 Organizational Structure

1.3 Volume of Operations

1.4 Technology Landscape (Current Systems)

1.5 Key Operational Workflow – A Simple Case Lifecycle

2.1 Legacy Systems and the Reality of Inflexibility

2.2 The Hidden Costs of Scale

2.3 The Illusion of “All-in-One” Systems

2.4 Enter Modular Thinking

2.5 This Is Why Odoo Is a Useful Starting Point

3.1 Not Because It's Perfect, Because It's Flexible

3.2 Prototyping at the Speed of Thought

3.3 The Power of Building on What Already Exists

3.4 Where Odoo Starts to Fall Short

3.5 The Mindset Shift: From Ownership to Interoperability

4.1 The Problem with How Incidents Are Reported Today

4.2 Deconstructing the Incident Lifecycle

4.3 What If Incident Reporting Was Just a Collection of Apps?

4.4 The Odoo Concept Model

4.5 Where This Model Could Go Next

5.1 Framing the Scenario

5.2 Step 1: Intake and Registration

5.3 Step 2: Officer Assignment and Escalation

5.4 Step 3: Investigation Records and Timeline Tracking

5.5 Step 4: Reporting and Decision Outputs

5.6 Step 5: Feedback and Review Loop

5.7 Summary of Concept Flow

6.1 Not Everything is a Perfect Fit — and That’s the Point

6.2 Modularity is a Double-Edged Sword

6.3 Speed to Prototype ≠ Readiness to Deploy

6.4 Transparency is Easier to Build than Trust

6.5 Odoo as a Thinking Tool, Not Just a Product

6.6 Final Reflection

7.1 Reform Begins with Visibility

7.2 System Design is Political

7.3 Platforms Like Odoo Can Be Catalysts, Not Solutions

7.4 Data Can be a Check on Narrative Power

7.5 Legacy Systems = Legacy Thinking

7.6 Reform Needs Builders and Bureaucrats

Section 1: Understanding the NYPD – A System of Systems

The New York Police Department is more than just a law enforcement body; it’s a living, breathing system made of thousands of moving parts. To even attempt to rethink or rebuild parts of it even in simulation, one must first understand its scale, scope, and interdependencies.

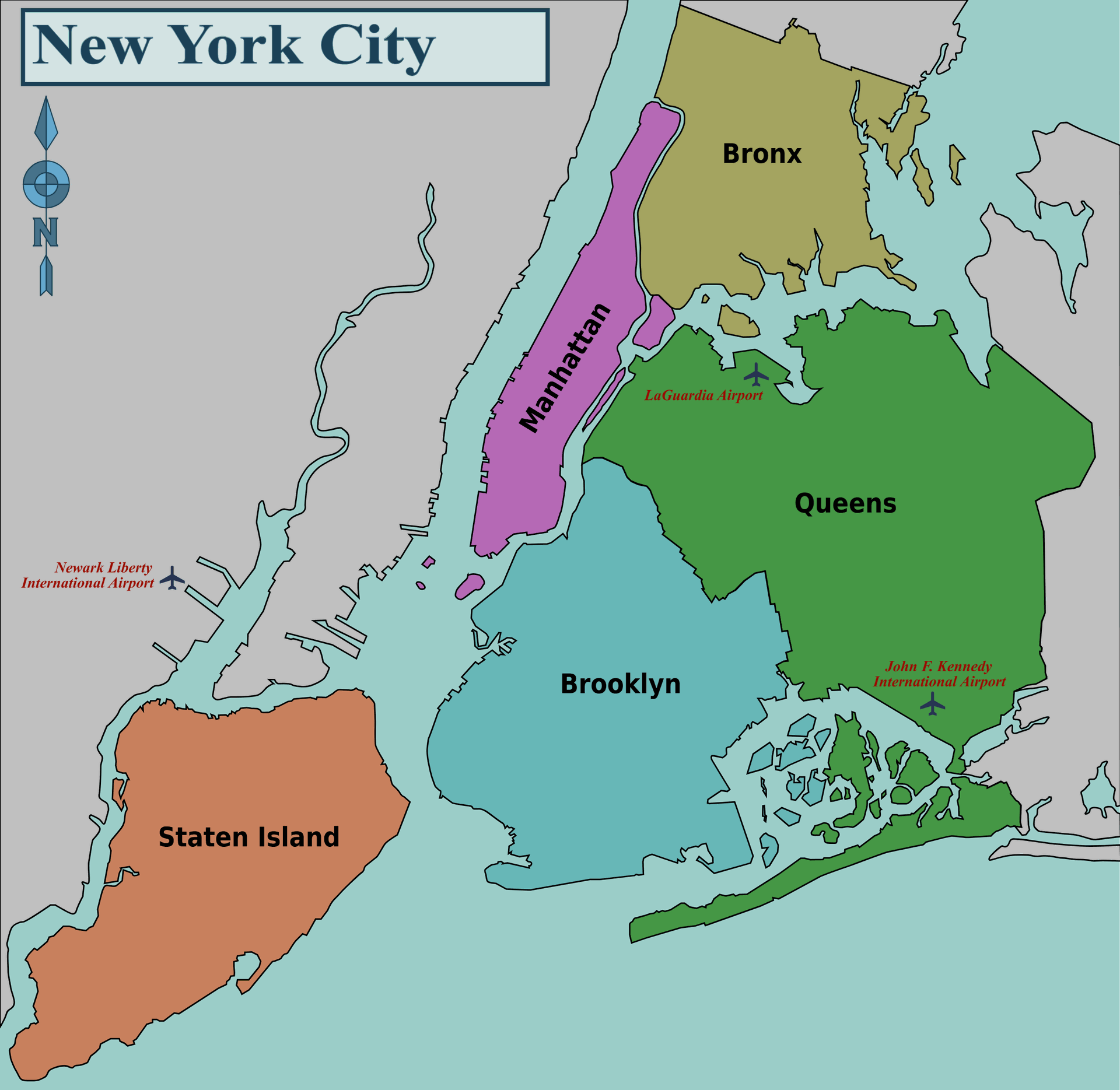

1.1 Size and Personnel

Founded: 1845

Total Employees: ~55,000

- Sworn Officers: ~35,000

- Civilian Employees: ~19,000+

Rank Structure:

- From Police Officers → Detectives → Sergeants → Lieutenants → Captains → Inspectors → Chiefs → Commissioner

Jurisdiction: Entire NYC (~8.5 million population)

image : Wikimedia commons

1.2 Organizational Structure

The NYPD is not one unified monolith, it is a constellation of specialized units:

- Patrol Services Bureau – Day-to-day city policing

- Detective Bureau – Handles investigations across homicides, narcotics, cybercrime, etc.

- Transit Bureau – Manages crimes and operations in subways

- Housing Bureau – Focuses on public housing projects

- Counterterrorism Bureau – High-level intelligence and threat assessment

- Special Operations – Emergency service unit, aviation, harbor patrol, etc.

- Internal Affairs – Oversight and accountability within the department

Each of these bureaus has its own protocols, data, operations, and chain of command.

1.3 Volume of Operations

911 calls

per year

Arrest Made annually

100k+Active Investigations

25k+Public complaint per day

1000+Precincts

77Vehicles

9000CCTV Cameras

25k+The scale of activity inside NYPD is staggering:

- 911 Calls per Year: Over 10 million

- Arrests Made: Hundreds of thousands annually

- Investigations Active at Any Time: Tens of thousands(exact data not available)

- Public Complaints Logged: Thousands per day

- Precincts: 77, each a world in itself

- Vehicles: ~9,000+ units

- CCTV Cameras: Thousands across citywide integrated systems(exact data not available)

These numbers don’t just reflect volume, they represent millions of workflows, approvals, handoffs, and decisions made daily.

1.4 Technology Landscape (Current Systems)

Over the years, NYPD has adopted and integrated a wide array of technology platforms:

- CAD (Computer Aided Dispatch) – For managing 911 calls and dispatching officers

- RMS (Records Management System) – To maintain logs of reports, complaints, arrests

- Domain Awareness System (DAS) – Massive network of cameras, sensors, analytics developed with Microsoft

- eJusticeNY – Statewide platform for criminal justice data access

- Internal Mobile Apps – Officers use department-issued smartphones for instant access to criminal records and reporting tools

- ShotSpotter, NYPD Shield, and dozens of niche systems power specific missions

Despite this, much of the NYPD still relies on manual processes, paper trails, disconnected systems, and legacy architecture.

1.5 Key Operational Workflow

A Simple Case Lifecycle

1

An event

occurs

2

911 is

called

3

An officer is dispatched

4

The officer writes an incident report

5

The report moves up the chain

6

Detectives

(if involved)

Let’s understand the most basic yet essential flow in the department: an incident report.

- An event occurs — a robbery, a noise complaint, a suspicious person.

- 911 is called, and the event is logged by the dispatcher.

- An officer is dispatched and responds on-site.

- The officer writes an incident report—sometimes digitally, sometimes still on paper.

- The report moves up the chain, and is either closed, escalated, or investigated.

- Detectives (if involved) take over, and parallel systems begin—court filings, evidence collection, etc.

This one sequence involves at least 5 systems, 3 levels of review, and multiple departments—and it’s just the beginning of a case.

Why This Understanding Matters

Before writing code, building dashboards, or designing forms, this is what developers must understand:

The NYPD isn’t just data. It’s context, human decision-making, and overlapping missions. The act of building a system here is not a software project; it is a systems design challenge.

Section 2: The Problem with Monoliths and the Need for Modular Thinking

For most of the 20th century, public institutions like the NYPD adopted a familiar approach to technology: build large, centralized, top-down systems that attempt to control every variable. This approach was logical at the time. With limited tech infrastructure and rigid chains of command, monolithic systems promised uniformity, scale, and control.

But today, those promises have become pain points.

2.1 Legacy Systems and the Reality of Inflexibility

Many of the NYPD's core systems like RMS, CAD, or even their internal ticketing systems were designed decades ago. They have grown over time but rarely evolved. They’re built on outdated assumptions:

- Officers are always at desks

- Data doesn’t need to be portable

- Every new requirement is a new form or table

- Integrations are exceptions, not defaults

As a result, even simple changes—like updating a workflow for domestic abuse reporting—can take months or even years.

2.2 The Hidden Costs of Scale

A system with tens of thousands of users (officers, clerks, admins) is bound to be resistant to change. That’s not just bureaucracy, it’s survival. If a form changes, thousands must be retrained. If a dashboard crashes, investigations halt.

This leads to:

- Tech paralysis – The fear of change outweighs the desire for innovation

- Workarounds – Officers using paper forms or WhatsApp groups for faster response

- Duplication of work – Same data being entered in multiple systems

- Audit challenges – Fragmented logs and accountability gaps

2.3 The Illusion of “All-in-One” Systems

Many enterprise vendors pitch “end-to-end” solutions to government agencies. But there’s a problem: real-world institutions don’t operate end-to-end. They operate in parts—parts that must evolve independently, integrate easily, and be updated without breaking everything else.

An “all-in-one” system, once deployed, often becomes a single point of friction instead of a platform for innovation.

2.4 Enter Modular Thinking

What if we stopped trying to build systems that did everything?

What if we started building modules that each solve one specific problem—really well—and connect through clear, open standards?

Modular thinking doesn’t mean “less power.” It means more adaptability, more speed, and more alignment with reality.

Imagine:

- One lightweight system for incident reporting

- Another system for investigation tracking

- A third for legal case management

- A dashboard layer that unifies views without centralizing data storage

Each part is replaceable. Each part is maintainable. And most importantly, each part is understandable.

2.5 This Is Why Odoo Is a Useful Starting Point

No, Odoo cannot manage emergency dispatches or parse facial recognition feeds.

But what it can do is:

- Model human workflows

- Track approvals and escalations

- Store structured records

- Generate reports and analytics

- Serve as a controlled interface between departments

- Rapidly prototype modules to test ideas

Odoo becomes the sandbox, a place to think clearly, build iteratively, and test assumptions without the cost of full system migration.

We start with something simple—like the incident reporting system—and treat it as a module.

Section 3: Why Explore with Odoo?

When you’re designing systems for institutions as complex as the NYPD, your first instinct might be to look for purpose-built public safety software. And rightly so—those systems exist. They are powerful, feature-rich, and field-tested.

But they also come with weight:

🚧 High cost of customization

🚧 Long procurement cycles

🚧 Vendor lock-in

🚧 Resistance to experimentation

What we needed for this phase wasn’t a product. We needed a platform, a thinking space. And that’s where Odoo comes in.

3.1 Not Because It's Perfect, Because It's Flexible

Odoo is not a public safety solution. It was never meant to be one. It was designed to handle business workflows—sales orders, inventory, HR approvals, timesheets. But underneath its surface lies a surprisingly powerful toolset:

- A robust ORM (Object-Relational Mapping) layer

- A modular architecture

- Workflow engine for approvals, escalations, and routing

- Access control systems for multiple user types

- Built-in reporting and dashboards

- RESTful APIs for integration with external systems

It’s not what Odoo does out-of-the-box that matters, it’s what it lets us build with clarity and speed.

3.2 Prototyping at the Speed of Thought

Public sector systems are often locked in endless cycles of requirement gathering, committee review, and vendor negotiations—before a single screen is built.

Odoo flips this process.

Because it’s open-source and modular, we can go from concept to working prototype in days, not quarters. We can:

- Test UI flows with real users

- Simulate data models and permissions

- Build approval paths without custom code

- Show, not tell

This is not just faster, it’s smarter. You don’t argue about what a system should look like. You build it, test it, and let feedback shape it.

3.3 The Power of Building on What Already Exists

Odoo comes with 100+ official apps and thousands more from the community:

- CRM

- Helpdesk

- Project Management

- Document Management

- Surveys

- eSignatures

- Portals

These aren’t just business tools, they’re building blocks. For example:

Helpdesk

Survey

Document

- Odoo’s Helpdesk module can be reimagined as a public complaint system

- Surveys can be used for witness statements or follow-ups

- Document Management can house digital evidence or investigation files

By repurposing existing tools, we accelerate development without sacrificing structure.

3.4 Where Odoo Starts to Fall Short

We must be honest here. Odoo has limits—serious ones, when it comes to:

- Real-time dispatch coordination

- GIS integration with city infrastructure

- Mobile-first, offline-capable apps for officers in the field

- Forensic data analysis or big-data processing

- Compliance with criminal justice security standards (e.g., CJIS)

These are not things we expect Odoo to solve. Instead, we design around them:

🛠️ Use Odoo to orchestrate workflows

🔗 Use external tools for real-time systems

🧩 Connect everything through APIs and clear boundaries

3.5 The Mindset Shift: From Ownership to Interoperability

Government IT often falls into the trap of thinking: “If we buy one big system, everything will work together.”

But in 2025, the better approach is:

“If we build clear interfaces, everything can work with everything.”

Odoo becomes part of a network of tools. It handles the boring but important stuff: who did what, when, and what happens next.

Section 4: Reimagining Incident Reporting – A Modular Blueprint

4.1 The Problem with How Incidents Are Reported Today

Today, incident reporting is often delayed, siloed, and painful to update. Officers may fill out multiple forms across disconnected systems—paper, desktop apps, legacy terminals—each one demanding redundant input. Small mistakes create big delays. The workflow, in many departments, has not evolved with the pace of policing.

4.2 Deconstructing the Incident Lifecycle

To rebuild incident reporting, we must first break it down. Every case follows a pattern:

- A triggering event (911 call, officer observation)

- A field report (often verbal, sometimes on paper, rarely structured)

- An incident entry

- Classification and routing

- Investigative updates

-

Closure and archival

Each step touches multiple roles and systems. By viewing it modularly—not as a giant form, but as a sequence of connected micro-events—we start to see the architecture for a better solution.

4.3 What If Incident Reporting Was Just a Collection of Apps?

Imagine a system where:

- Officers report incidents using a mobile-friendly “Field Log” app

- Supervisors classify and tag reports in a “Desk Review” module

- Detectives add evidence and interviews through a “Case Diary”

- Legal teams receive structured summaries via an “Export to DA” workflow

Each app serves a purpose. Each has a clear user and context. Together, they build the full story.

4.4 The Odoo Concept Model

Here’s what we explored:

- Field Entry App: A customizable form that can adapt based on incident type. Trigger-based auto-routing included.

- Case Tracking Dashboard: Dynamic filters for open, assigned, or aging cases. Role-based access baked in.

- Evidence Log: Tracks items, status, location, and chain of handlers.

- People Module: Not just suspects—also victims, witnesses, and officers. With roles, links, and timelines.

- Timeline Builder: Every update, every note, every file—chronologically organized.

Every module was mapped out, scoped, and imagined inside Odoo’s architecture.

4.5 Where This Model Could Go Next

This concept opens the door to smart additions:

- Voice-to-text reporting in the field

- Integration with bodycam footage logs

- Notifications for follow-ups and deadlines

-

API endpoints to sync with court systems

With modular thinking, each new feature becomes a building block, not a rebuild.

Section 5: Designing the Prototype- A Narrative Flow

5.1 Framing the Scenario

Imagine a citizen walking into a police precinct in Brooklyn to report a missing person. Or an officer in Queens using a mobile device to log an incident on the field. These aren't rare cases, they’re daily routines in the NYPD’s operational life. And while the stakes differ from report to report, the underlying process has one thing in common: it must start clean, flow fast, and feed into a system that scales.

5.2 Step 1: Intake and Registration

At the front desk, a clerk or officer initiates the first step — registering a case. In Odoo, this can be modeled using the Helpdesk or CRM module as a base. Forms can be adapted to gather incident details, individual profiles, timestamps, and categorization (e.g., criminal, civil, lost and found, etc.). Drop-down lists, conditional logic, and duplicate detection could help streamline this intake while ensuring data consistency.

Conceptually, we explore how much of this user journey can be translated using default views, custom fields, and minimal backend scripting.

5.3 Step 2: Officer Assignment and Escalation

Once registered, the next action is assignment. Either the case stays local or it gets escalated to a specialized department, a detective, or even another precinct. Here, Odoo’s Project and Task Management structure offers a framework for modeling escalation logic. Tags, stages, and workflows can help visualize where a case is in the chain of responsibility.

What we’re exploring is not how to code it perfectly but whether Odoo’s architecture naturally supports role-based flow control and branching logic.

5.4 Step 3: Investigation Records and Timeline Tracking

As work progresses, each interaction — witness statements, evidence collection, field reports — needs to be logged chronologically. This is where Odoo’s Notes, Activities, and even Timesheets become useful for building an audit trail.

We try mapping a simplified version of the case timeline: Can a series of notes, checklists, and uploads represent the evolving investigation? Can permissions restrict visibility as complexity grows?

5.5 Step 4: Reporting and Decision Outputs

Eventually, every case reaches closure — solved, unsolved, archived, or transferred. From an operational view, this means generating a summary, locking edits, and triggering review processes. Odoo’s Reporting tools offer baseline options for templates, exports, and status breakdowns.

Here, the idea is to observe how effectively the system supports output logic. What would it take to integrate templates for legal handoffs or statistical dashboards for department heads?

5.6 Step 5: Feedback and Review Loop

One underutilized feature in many real-world policing systems is the feedback loop — both from the public and internally. Odoo’s Survey, Website, or Email modules provide a way to test if such review systems can be built in.

Not just for accountability, but for identifying patterns, bottlenecks, and user friction. We examine whether a modular system can support dynamic listening without becoming bloated.

5.7 Summary of Concept Flow

We’re not claiming every step above fits perfectly into Odoo’s existing mold. But by working through a real-world narrative — from intake to closure — we’re able to test how modular ERP thinking behaves under pressure.

The goal here is architectural: to trace a concept end-to-end and understand what gets easy, what needs tweaking, and where we might hit a wall.

Section 6: What We Learned from the Design Exercise

6.1 Not Everything is a Perfect Fit and That’s the Point

Odoo was never built to simulate a law enforcement agency. Its DNA is business logic: leads, orders, projects, inventory. But this exercise shows something deeper — many public sector systems, at their core, are built around workflows, permissions, status updates, and data visibility. That’s exactly what Odoo excels at.

The case intake process? Similar to CRM. Officer reassignment? Feels like task delegation. Evidence logging? Not unlike document management or issue tracking. When abstracted, even complex NYPD flows start resembling ERP logic trees.

6.2 Modularity is a Double-Edged Sword

What makes Odoo powerful is its modularity — you only install what you need. But in a system as interwoven as the NYPD, this means constant balancing: too much granularity, and you drown in configurations; too little, and your system becomes inflexible.

For example, should patrol logs be a separate module, or a sub-feature of incident reports? Should internal affairs and community complaints run on the same form architecture? These questions aren’t technical, they’re strategic.

6.3 Speed to Prototype ≠ Readiness to Deploy

We were able to model workflows quickly — that’s the charm of low-code. But scalability, fault tolerance, and institutional integration? Those don’t come out of the box. A system prototype might mimic NYPD operations at a precinct level, but what happens when you multiply that by 77 precincts, thousands of officers, real-time feeds, and external system dependencies?

This is where platform limits surface. The prototype helps locate those boundaries early.

6.4 Transparency is Easier to Build than Trust

Odoo makes it easy to build audit trails — who did what, when, and why. But no software can guarantee the human layer: the will to share, escalate, or act fairly. What the exercise reveals is that technical transparency is only one side of accountability.

Our system can log who closed a case, but it cannot fix the reason why the case was closed too early.

This reaffirms an uncomfortable truth: good systems support trust; they don’t create it.

6.5 Odoo as a Thinking Tool, Not Just a Product

Perhaps the most valuable insight wasn’t technical at all. It was epistemological. Using Odoo forced us to think in flows, roles, and logic steps. It became a way to interrogate the NYPD not as a static institution, but as a system-of-systems.

By simulating processes — even imperfectly — we learned to ask better questions:

Who decides what counts as a “case”?

When does human judgment override automation?

How should digital visibility differ by rank, department, or geography?

These aren’t database schema issues. They’re governance design questions.

6.6 Final Reflection

This wasn’t about building software. It was about learning through software.

Odoo became a cognitive mirror — helping us see which parts of NYPD’s structure are compatible with modern, modular design, and which parts resist translation.

In a world flooded with tech promises, this quiet kind of insight might be the most powerful thing we can take from a prototype.

Section 7: Implications – What Could This Mean for Real Reform?

7.1 Reform Begins with Visibility

Much of the debate around police reform centers on accountability, equity, and systemic transparency. But as we’ve learned through this modeling exercise, you can’t reform what you can’t see.

By reimagining the NYPD’s workflows through a structured, digital system like Odoo, we gain clarity on how information moves, who makes decisions, and where bias or inefficiency might enter. Reform isn't only about new rules, it's about new architecture that makes those rules trackable, enforceable, and reviewable.

7.2 System Design is Political

Every dropdown, every permission level, every status flag is a design choice — and every design choice encodes values. Should precinct commanders be able to override civilian complaints? Should officers see internal affairs inquiries involving their colleagues?

These are not technical questions. They are questions about power, hierarchy, and trust.

The act of digitizing NYPD processes forces those values into the open. That’s not just helpful, it’s necessary.

7.3 Platforms Like Odoo Can Be Catalysts, Not Solutions

Odoo will not "solve" policing. No software can. But platforms like Odoo can make experimentation cheaper, iteration faster, and pilot programs more honest.

Imagine cities being able to prototype reforms before launching them — testing how disciplinary dashboards might affect officer behavior, or how real-time complaint routing could reduce escalation.

The goal isn’t perfect software. It’s institutional learning at scale.

7.4 Data Can be a Check on Narrative Power

In high-stakes public institutions, stories matter: who said what, what happened next, what got buried. But systems like the one we modeled can produce a counterweight — timelines, logs, cross-checks.

When used ethically, this data doesn’t replace stories. It strengthens the public’s ability to validate or challenge them.

In a reform context, structured data becomes a civil right.

7.5 Legacy Systems = Legacy Thinking

Most of the NYPD's existing tech stack is fragmented, aging, or inaccessible. That’s not just an IT problem, it’s a mindset problem.

Legacy systems entrench silos, limit transparency, and make it easy to say “we can’t change that.” Prototyping on a modern, open-source platform offers a mental reset. It asks: What if this process wasn’t constrained by old software? What if we started from first principles?

7.6 Reform Needs Builders and Bureaucrats

Real transformation won’t come from protests alone. It won’t come from software alone either. It will require cross-disciplinary collaboration — policy thinkers who understand workflows, and technologists who understand human systems.

This project isn’t a blueprint for replacing the NYPD’s software. It’s a call to invite more builders into the conversation about public safety.

Conclusion: The Blueprint is the Beginning

This prototype is not a product. It's a provocation. By mapping the NYPD’s institutional structure onto a modular, open-source platform like Odoo, we’ve illustrated something deceptively simple: that even the most complex public systems can be made legible, interrogable, and redesignable. Reform isn’t just about political will or legal battles — it’s also about the capacity to see what needs changing and test what might work better.

Software can’t replace accountability, but it can help us build the infrastructure for it. If we want a more just, transparent future of policing, we need to stop asking “what can we fix?” and start asking “what can we redesign?” This isn’t about the NYPD alone. It’s about the courage to prototype the public sector.

Written by Faisal Maniar and Umar Maniar